Cruz Azul

| |||

| Full name | Club de Futbol Cruz Azul S.A. de C.V. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | La Máquina (The Machine) Los Celestes (The Sky-Blues) Los Cementeros (The Cement Makers) Las Liebres (The Hares) Los de La Noria (The Men from La Noria) | ||

| Short name | CAZ | ||

| Founded | 22 May 1927 | ||

| Ground | Estadio Olímpico Universitario | ||

| Capacity | 58,445[1] | ||

| Owner | Cooperativa La Cruz Azul, S.C.L. | ||

| President | Víctor Velázquez | ||

| Manager | Vicente Sánchez (interim) | ||

| League | Liga MX | ||

| Apertura 2024 | Regular phase: 1st Final phase: Semi-finals | ||

| Website | cfcruzazul.com | ||

|

| |||

Club de Futbol Cruz Azul S.A. de C.V., commonly referred to as Cruz Azul, is a professional football club based in Mexico City, Mexico. It competes in the Liga MX, the top tier of Mexican football. Founded in 1927 in Jasso, Hidalgo, the club officially moved to Mexico City in 1971, where it had already registered a great presence and activity since its beginnings. Estadio Azteca, the nation's largest sports venue, served as their home venue until 1996, when they moved to the Estadio Ciudad de los Deportes, which was renamed Estadio Azul. After 22 years, the team returned to the Azteca following the conclusion of the 2017–18 Liga MX season. Its headquarters are in La Noria, a suburb within Xochimilco in the southern part of Mexico City.[2]

Domestically, the club has won nine league titles, four Copa MX, three Campeón de Campeones, and holds a joint-record with one Supercopa de la Liga MX and one Supercopa MX. In international competitions, the club's six titles makes it the second-most successful club in the history of the CONCACAF Champions Cup/Champions League, the most prestigious international club competition in North American football. Cruz Azul also holds numerous distinctions, including being the club with the most league runner-up finishes (12),[3] the first CONCACAF team to reach the final of the Copa Libertadores—the most prestigious club competition in South American football—losing on penalties to Boca Juniors in 2001,[4] achieving a rare continental treble in the 1968–69 season by winning the Primera División, Copa México and CONCACAF Champions' Cup, becoming the first CONCACAF club and third worldwide to accomplish this feat,[5] and becoming the first club worldwide, and one of only five, to have won the continental treble twice.[6]

In its 2014 Club World Ranking, the International Federation of Football History & Statistics placed Cruz Azul as the 99th-best club in the world and the third-best club in CONCACAF.[7] According to several polls published, Cruz Azul is the third-most popular team in Mexico, behind only C.D. Guadalajara and Club América.[8] It is also the second most supported team in its area, Greater Mexico City, behind América and ahead of Pumas UNAM.

History

[edit]Background and foundation

[edit]Carlos Garces López was a footballer and athlete, included in the Mexico national team for the 1924 and 1928 athletics and football.[9] As a midfielder, he was part of Club América's founding squad and was a key player to their dominance of the Primera Fuerza in the mid-1920s.[10][11] Garces López was included in the debut Mexico national football team in 1923, playing in Mexico's debut series of official international matches against Guatemala.[12][13] At the time, football in Mexico was not a lucrative occupation. Garces López was a licensed dentist providing dental care at the cement company Cooperativa La Cruz Azul, S.C.L. located in the small town of Jasso, Hidalgo. He would travel regularly to Mexico City from Jasso to train and play for América.[14]

In 1925, Cooperativa La Cruz Azul had voted to establish a company baseball team as the sport was popular in the town of Jasso.[15] Garces López personally lobbied for many months to change the official company sport to football. American employees initially receiving resistance but the company directors relented to a referendum for determination of the company team's main sport. The March 22, 1927 election favored football.[16] Cooperativa La Cruz Azul replaced the company baseball diamond with a football pitch. The football team was officially established two months later on May 22 where Garces López was appointed head coach.[14]

Amateur era (1927–1961)

[edit]Initially, Cruz Azul played in local tournaments organized by the company against teams representing towns neighboring Jasso. The team was composed solely of company workers for the next three decades. The club was widely successful in amateur tournaments during the 1930s and 1940s, winning 15 consecutive state level league titles.

Establishment as a co-operative (1931–1934)

[edit]By 1931, Cooperativa La Cruz Azul had experienced a series of economic troubles during the Great Depression. Due to the loss of demand and production of cement and other construction materials, the company faced bankruptcy and was bought by cement company La Tolteca on March 1, 1931, for 1 million pesos. The liquidation of Cooperativa La Cruz Azul was anticipated by 192 workers of the company who unionized and sued the executives of the company to prevent the transfer of the property which was set for October 15, 1931. The government of Hidalgo ruled in favor of the workers after it was shown La Tolteca had premeditated intentions of liquidation. The workers assumed control of the industrial facilities on November 2. On May 21, 1932, the governor of Hidalgo, Bartolomé Vargas Lugo, decreed the 192 workers of Cooperativa La Cruz Azul as collective owners of the plant, exercising eminent domain. Part of the agreement, all 192 workers who assumed responsibility of the plant agreed to pay the state of Hidalgo 1.3 million pesos over the course of 10 years. The company changed its name to Cooperativa Manufacturera de Cemento Portland La Cruz Azul, S.C.L, reestablishing itself as a cooperative on January 29, 1934. The debt was settled on November 2, 1941, 10 years after workers took ownership of the plant. In celebration, Cruz Azul organized a match against R.C. España, that ended in a 0–0 draw.[17][18][19][20][21]

This scenario of the club's formation encourages its working-class facade.[22][20][23]

Success in amateur competitions (1932–1952)

[edit]From 1932 to 1943, Cruz Azul won 15 consecutive league titles in an amateur league in the state of Hidalgo. On 8 different occasions, the club represented the state of Hidalgo in national amateur tournaments. From the mid-1930s to the late 1940s, the club regularly traveled to Mexico City to face the reserve teams of Atlante, Necaxa, Marte, and R.C. España, playing at Parque Necaxa to great success.[24][25] By 1937, Cruz Azul had garnered a considerable following both in Hidalgo and Mexico City.[26][27][18][25] Around this period in time Guillermo Álvarez Macías began playing on the team as a midfielder.[28]

Foundations for professional status (1953–1960)

[edit]On December 10, 1953, Guillermo Álvarez Macías was appointed general manager of Cooperativa La Cruz Azul. He had been employed at the cooperative since 1931 at the age of 12 when his father died. Initially employed as an automotive mechanic, Álvarez Macías spent over two decades at the company, rising through the ranks.[29] A self-proclaimed socialist, Álvarez Macías laid plans to transform the cooperative into a functioning town, building schools, restaurants, paving roads, in hopes to modernize and "share social and economic progress, to raise the standard of living of the worker and his family."[30][29] In his goal to promote social well-being among members of the co-op, Álvarez Macías invested into cultural and recreational activities.[29] This included investing much more into the football club whose proceeds were used to provide the worker-players with better living conditions.[28]

In 1958, team captain and machinist, Luis Velázquez Hernández, served as the club's ambassador to the Mexican Football Federation to lobby for official membership on the club's behalf. Velázquez Hernández met Paulino Sánchez in Mexico City, who had ties to prominent football executives. They met with Joaquín Soria Terrazas and Ignacio Trelles to discuss membership in the federation for the club. Sánchez vouched in favor of Cruz Azul, citing their continual success in the amateur and reserve tournaments. Much to the displeasure of Álvarez Macías who asserted the club was not ready for professional football.[31][32][17][33][34]

In preparation for federation membership, Paulino Sánchez assumed the position as head manager of the club. Due to regulations, teams were required to have a reserve team. Lafayette, a club experiencing financial troubles located in Colonia Moctezuma, had many talented players that could potentially be Cruz Azul's reserves. Under the recommendation of Sánchez, Cruz Azul purchased the Lafayette team. The acquisition was completed sometime in 1960.[35][36][37] Plans to construct a club stadium that complied to the standards set by the Mexican Football Federation were conceived in 1960.[38] In 1961, ground broke to construct Estadio 10 de Diciembre and finished in 1963.[39][40]

Despite not possessing federation membership and due to Sánchez's personal contacts, Cruz Azul was invited to compete in the 1960-61 edition of Copa de la Segunda División de México, a competition sanctioned by the Mexican Football Federation. The club's debut game was played on April 2, 1961, in Jasso against Zamora, ending in 2–1 in favor of Cruz Azul. The second leg was played on April 9, 1961, ending in a 3–3 draw. They faced Querétaro in the next round winning 1–0 on aggregate. Cruz Azul was eliminated by UNAM. Following their impressive performance in the cup, the Mexican Football Federation granted Cruz Azul an opportunity to register as a professional team.[41][37][42]

Professional level and rapid rise to prominence (1961–1968)

[edit]The club was officially registered to compete in the nation's second tier professional league for the 1961–62 season.[43]

Due to the regulations by the Mexican Football Federation that prohibited the official usage of company names by clubs, the club changed its name to Cooperativa Cruz Azul from Cemento Cruz Azul [44]

Promotion to Primera División (1964)

[edit]

Jorge Marik, a Hungarian coach who previously managed Atlas and Atlante, signed on to manage the club in 1961.[45] Cruz Azul won a direct promotion to Primera División after Marik led the club to the 1st position on the general table with 45 points (19 wins, 7 draws, and 4 losses) in the 1963–64 Mexican Segunda División season.[46]

Following the club's promotion, Estadio 10 de Diciembre underwent renovations on March 6, 1964, rebuilding the wooden stands and dressing rooms which were compliant to regulations.[39]

Cruz Azul finished their first season in the top flight, the 1964–65 Mexican Primera División season, in 8th place with 10 wins, 9 draws, 11 losses.[47]

After poor results, Marik left the club after the 1965–66 Mexican Primera División season where Cruz Azul finished in 13th place out of 16 teams on the league table.[48] Walter Ormeño became the team's interim coach, managing 3 games, before the club signed Raúl Cárdenas October 20, 1966.[49][50][51]

Establishment in the top flight (1969–1980)

[edit]Domination of Primera División (1969–1975)

[edit]1968–69 season: first championship, treble

[edit]During the 1968–69 season under the direction of Cárdenas, Cruz Azul won their first Copa México, their first Primera División title, and their first CONCACAF Champions' Cup.[52] After only 4 years in the nation's top flight, Cruz Azul managed to complete a treble, being the first club to do so in not only Mexico but in the CONCACAF region as well.[53]

1970–1980

[edit]Cruz Azul finished in second place on the general table for the 1969–70 Mexican Primera División season.[54] The club was awarded the 1970 CONCACAF Champions' Cup on December 15, 1970, after Saprissa and Transvaal withdrew from the second phase of the competition in September citing economic issues.[55][56]

Between 1970 and 1980, Cruz Azul led the Primera División with six league tournament championships; four under Cárdenas and the last two under Ignacio Trelles. This powerful version of the team earned the nickname La Máquina Celeste (The Blue Machine), which continues as one of the official nicknames of the team.

On December 18, 1976, Guillermo Álvarez Macías died of a heart attack at the age of 56 while awaiting President Portillo for a meeting.[44][57]

First drought (1981–1997)

[edit]Throughout the 1980s, Cruz Azul remained one of the most competitive teams in the league. Despite their consistent form and financial wealth, the club was unable to obtain a title. This drought would last for another 17 years.

Billy Álvarez presidency

[edit]In 1988, Guillermo Héctor Álvarez Cuevas, the son of the late Guillermo Álvarez Macías, assumed the position of general manager at the cooperative Cooperativa La Cruz Azul and presidency of Cruz Azul.[58]

1990–1995

[edit]

For the 1991–92 season, Cruz Azul signed Carlos Hermosillo. An América icon who was fundamental to America's 1988–89 league championship victory against Cruz Azul, Hermosillo's signing was met with ambivalence by the club's supporters.[59] Hermosillo, however, quickly established himself as an integral part of the team where he was the league's top goal scorer for 3 consecutive years (1993–94, 1994–95, 1995–96 – 27, 35, 26 goals respectively).[60]

In the 1994–95 season, the club finished 3rd in the league's overall table and reached a league final for the first time in 6 years where they were defeated 3–1 on aggregate by Necaxa.[61]

1996–1997: end of drought and second treble

[edit]July 20 of 1996 marked the end of a 16 year long championship drought for Cruz Azul. The team managed by Víctor Manuel Vucetich won the CONCACAF Champions' Cup single round-robin tournament held in Guatemala City.[62] Cruz Azul finished 1st on the table after defeating Seattle Sounders 11–0 at Estadio Flores.[63] Vucetich also lead Cruz Azul to a Copa México title, winning the 1996–97 Copa México at the Estadio 10 de Diciembre after defeating Toros Neza 2–0.[64]

Under the management of Luis Fernando Tena, Cruz Azul won the CONCACAF Champions' Cup on August 24, 1997, for the second consecutive year after defeating LA Galaxy 5–3 in the final.[65] On December 7, 1997, Cruz Azul, who finished 2nd in the general standings of the league table, won the Invierno 1997 league tournament the against table leaders León via golden goal. This marked an end to the club's 17 year long league drought as well as achieving Cruz Azul's second continental treble.

The second leg of the series is largely remembered in part of a self-admittedly inexplicable act of aggression committed by León's goalkeeper Ángel Comizzo towards Carlos Hermosillo that handed the championship title to Cruz Azul.[66] During the 15th minute of the first half of extra time, Comizzo shoved and kicked Cruz Azul striker Hermosillo in the face while inside the penalty box. Referee Arturo Brizio only witnessed the shove but did not see the kick as he turned his head away when Comizzo kicked Hermosillo. The penalty was called in favor of Cruz Azul while Comizzo did not get sent off.[67] Hermosillo, whose face was bleeding profusely, took the penalty kick and scored. As the golden goal rule applied, Cruz Azul won the match and their eighth league title.[68][53]

Second trophy drought (1998–2013)

[edit]Copa Libertadores 2001

[edit]In 2001, Cruz Azul was invited to a tournament between select Mexican and Venezuelan teams that would then compete in the Copa Libertadores, a tournament of the best South American teams. The two best teams of this qualifying tournament earned immediate placement on the roster.

Cruz Azul was one of the seeded teams and reached the 2001 Copa Libertadores final match. Cruz Azul started the tournament in Group 7 along with Sao Caetano, Defensor Sporting, and Olmedo. Cruz Azul finished as leader of the group with 13 points. In the round of 16 Cruz Azul faced Cerro Porteño. The first leg was played in Asunción, where Cruz Azul lost 2–1. The second leg was played in Mexico City, where Cruz Azul won the game 3–1. The aggregate score was 4–3 in favor of Cruz Azul and they moved on to the quarterfinals.

In the quarterfinals, Cruz Azul faced River Plate of Argentina. The first leg of the match was played in Buenos Aires and ended in a 0–0 draw. The second leg was played in Mexico City and Cruz Azul won 3–0. Cruz Azul was having a great run and faced Rosario Central at the semifinals. The first leg was played in Mexico City and Cruz Azul won the game 2–0. The second leg was played in Rosario, a very exciting match that ended in a 3–3 draw in favor of Cruz Azul due to the 2–0 victory in the first leg.

In the final match, Cruz Azul played against the Argentine giants Boca Juniors. Cruz Azul lost at home the first leg 1–0, but came back to win the second leg with the same score at Boca's La Bombonera stadium with Paco Palencia scoring the goal. Until then, no team had ever won a Copa Libertadores final match there. After overtime, the championship was decided by penalty kicks where Boca Juniors prevailed. Still, Cruz Azul surprised everybody with the unprecedented feat of reaching the final and defeating established Argentinian teams such as Rosario Central and River Plate.

2005 abduction of Rubén Omar Romano

[edit]After leaving a pre-season practice session on July 16, 2005, manager Rubén Omar Romano was cornered by two stolen vehicles and abducted by 5 men. A ransom note was later found demanding of Romano's family $500,000.[69] Assistant coach Isaac Mizrahi managed the team during Romano's absence.[70] After 65 days, Romano was found and rescued unharmed. Federal agents raided a house in a poor neighborhood where Romano and his kidnappers were situated.[71] The agents arrested 7 conspirators who were under the orders of convicted abductor Jose Luis Canchola.[71]

During the hostage incident, the club had decided to not renew Romano's contract upon the end of Apertura 2005 and instead offered the position to Mizrahi following stellar results.[72] Mizrahi accepted the offer while Romano was in captivity. Romano stated he felt betrayed and his friendship with Mizrahi was severed.[73]

Series of runner-ups and last-minute losses (2008–2013)

[edit]The club was regularly regarded to be contenders for championship titles due to their formidable and financial stature in the league. Throughout this period in time however, Cruz Azul competed in many league and tournament finals only to finish runners-up.[74] In these championship matches, as well as regular season games, Cruz Azul initially would be favorites to win, often having the advantage over the opponent, but would ultimately draw or lose near the end of full stoppage time. As a result, the club garnered a negative reputation of being cursed and the club would often be subject to ridicule. The term cruzazulear, defined as "the act of losing a game after victory is practically assured", is used to describe Cruz Azul losing a match in the aforementioned manner beginning sometime in 2013. The usage of the term was so prevalent that it is officially recognized by the Royal Spanish Academy in 2020.[75][76][77]

Clausura 2008

[edit]During the Clausura 2008 season, the team played a great tournament, finishing in second place. The team won 9 games, had 4 draws and lost only 4 times. In the quarterfinals they played against the Jaguares losing 1–0 in the first leg and winning 2–1 in the second leg with goals of Pablo Zeballos and Miguel Sabah. They moved to the semifinals against the San Luis, the first leg was played in San Luis and Cruz Azul won 0–1 with a goal of Miguel Sabah. In the second leg, Cruz Azul and the San Luis played a formidable match that ended 1–1 with goals of Eduardo Coudet and Pablo Zeballos. In the final, Cruz Azul played against Santos Laguna, second place in the tournament. In the first leg, Cruz Azul lost 1–2 at home, and a 1–1 draw in the second leg meant that Santos were champions with a 3–2 aggregate score.[78]

Apertura 2008

[edit]For the Apertura 2008 season, Cruz Azul finished in 5th place on the overall table. The team had 7 wins, 5 draws, and 5 losses.

In the quarterfinals, Cruz Azul defeated Pumas UNAM with an aggregate score of 3–1, moving on to the semifinals against Atlante; the first leg was played in Mexico City, and Cruz Azul won 3–1. In the second leg, Cruz Azul tied Atlante 1–1 in Cancún, which meant that Cruz Azul reached the Final for the second consecutive time. In the final, Cruz Azul played against Toluca, both teams tied on winning Mexican titles (at that time with 8 each). The first leg played in Mexico City ended with a dramatic 0–2 with a victory for Toluca, and in the second leg, which was played at Estadio Nemesio Díez, Cruz Azul won 0–2, which put the aggregate score at 2–2, which meant extra time had to be played. No goals were scored in extra time and the match went into a penalty shootout, where Toluca won 7–6 over Cruz Azul and won the title, after Alejandro Vela missed his penalty, even though he was the one that scored the opening goal of the game for Cruz Azul. In the 72nd minute, César Villaluz was fouled in the penalty box and suffered a serious injury, but Cruz Azul were unable to substitute him as they had no remaining substitutes, so the team was forced to defend the scoreline with 10 men for almost fifty minutes, which possibly could´ve had a big outcome on the result, as well as the decision to not award a penalty.[79]

2008–09 CONCACAF Champions League

[edit]

The team qualified for the 2008–09 CONCACAF Champions League by finishing league runner-ups. In the first stage, they finished second in Group A, qualifying for the knockout stage. In the quarter-finals, they defeated Pumas UNAM 2–0 on aggregate; in the semi-finals, they defeated the Puerto Rico Islanders on penalties with 10 men, after coming back from a 2–0 loss in the first leg. In the final against Atlante, they lost the first game 0–2 and tied the second 0–0, losing on aggregate.[80]

Clausura 2009

[edit]

In the Clausura 2009, the team had the worst tournament in club history en route to a last-place finish. They accumulated just 13 points in 17 games, winning only two games, with seven draws and eight losses. The Club sacked their manager Benjamín Galindo with one game left in the Clausura. He was replaced for the remainder of the season by Robert Siboldi who was then coaching Cruz Azul's affiliate in Hidalgo.

Apertura 2009

[edit]

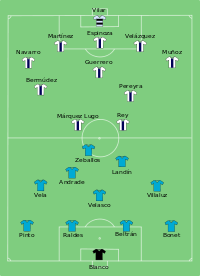

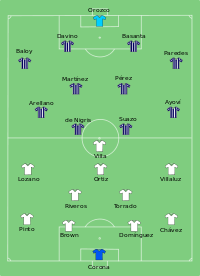

In the Apertura 2009, the team had signed Enrique Meza to manage the team and signed several players, including the best goalkeeper of the previous Mexican tournament José de Jesús Corona, Argentine striker Emanuel Villa, Ramón Núñez, and Emilio Hernández. The team finished the regular season in second place with 33 points, winning 11 games of 17 played, and qualifying for the playoffs; Villa was the top scorer of the tournament with 17 goals. In the quarter-finals, they beat Puebla 7–6 on aggregate, and in the semi-finals, they beat Monarcas Morelia 2–1 on aggregate. In the final, they lost to Monterrey 6–4 on aggregate, meaning this was now their third consecutive time failing to win a league finals.[81][82]

In April 2012, Cruz Azul changed their official name from Club Deportivo, Social y Cultural Cruz Azul, A.C. to simply Cruz Azul Fútbol Club, A.C.

2009–10 CONCACAF Champions League

[edit]In the 2009–10 CONCACAF Champions League, the team had a good tournament, finishing first in Group C and qualifying for the final stage of playoffs. In the quarter-finals, they defeated Panamanian team Árabe Unido 4–0 on aggregate, and then in the semifinal round, they played against the Mexico City rivals Pumas UNAM, losing the first leg 1–0 but winning the return leg 5–1 at Estadio Azul. In the final, against another Mexican club, Pachuca, they had the chance to win their 6th CONCACAF championship, winning the first game at home 2–1, but lost at Pachuca's home 1–0 with a last minute goal, meaning Pachuca won the championship by the away goals rule, and Cruz Azul missed the opportunity to participate in the 2010 FIFA Club World Cup.

Liga MX Clausura/Copa MX Clausura 2013

[edit]During the 2013 season, Cruz Azul started slow but regained confidence after beating Club América in the Copa MX semi-finals and winning the Copa MX final over the Atlante. After Cruz Azul won the Copa MX, their Liga MX performance improved and they were considered one of the contenders for the title due to a good streak. They would face bitter rivals the Club America in a historical final series of the "Clásico Joven." Cruz Azul was up 2–0 in aggregate when the Club America made a miraculous comeback with goals in the 89th from Aquilvado Mosquera and 93rd minute from Moises Munoz who was a goalkeeper of the second leg; Club America would go on to win 4–2 on penalties.

End of Second drought and CONCACAF Champions League win (2014–2019)

[edit]On April 23, 2014, after defeating Toluca, Cruz Azul won their 6th CONCACAF championship, a record at the time, and winning their first trophy in seventeen years.[83] This gave Cruz Azul a berth at the 2014 FIFA Club World Cup, where they would earn a fourth-place finish.[84]

From the Clausura 2014 to the Clausura 2017, Cruz Azul had been unable to qualify to the liguilla playoffs for six consecutive tournaments.[85] Cruz Azul qualified for the liguilla for the first time in three years in the Apertura 2017 season. However, they were eliminated in the quarterfinals by the América, who advanced as the higher-ranked seed, with an aggregate score of 0–0. On 27 November 2017, Cruz Azul announced that Paco Jémez would not renew his contract for the following season.[86][87]

In the Liga MX Clausura 2018 tournament, Cruz Azul ended up ranked 12th and failed to qualify for the liguilla. The club also finished last place in the group stage of the Clausura 2018 Copa MX. On 7 May 2018, the club announced director of football Eduardo de la Torre's contract had ended and would be replaced by Ricardo Peláez, former director of football for Club América.[88][89][90][91]

On 31 October, they would face Monterrey in the Apertura 2018 Copa MX Final, winning 2–0 with goals from Elías Hernández and Martín Cauteruccio. It was their first trophy in the tournament since 2013.[92]

Cruz Azul faced América in a rematch of the Clausura 2013 final for the Apertura 2018 final. The first leg was played on 13 December 2018 which ended in a scoreless draw. The second leg was played three days later and ended in a 2–0 victory for América. With this defeat, Cruz Azul extended its 21-year-old championship drought in the league for at least another season.

Administrative vicissitude (2020)

[edit]Indictment and ousting of board of directors

[edit]In May 2020, Guillermo Alvarez Cuevas, then president of the club, was indicted by Mexican authorities on multiple accounts of insurance fraud, racketeering, extortion, tax evasion, and money laundering.[93] On July 26, an arrest warrant was issued for Alvarez along with board directors Victor Manuel Garcés, Miguel Eduardo Borrell, and Mario Sánchez Álvarez for alleged ties to organized crime.[94][95] Alvarez subsequently resigned from his position at the club in August 2020 after 32 years as acting president.[96] Interpol is currently searching for Alvarez in 195 countries and as of June 2, 2021, remains at large.[97]

2020 season

[edit]On December 6, 2020, Cruz Azul faced UNAM on the second semi-final leg of the Guardianes 2020 Liga MX final phase. Although Cruz Azul had a 4–0 lead at the beginning of the second leg, they lost the match 0–4, thus tying in aggregate. Because UNAM won the clubs' week 17 match 1–0, they held the tiebreaker and advanced to the final.[98]

End of Drought (2021)

[edit]Following a disappointing end to 2020, Cruz Azul underwent significant changes ahead of the Guardianes 2021 tournament. The club appointed Juan Reynoso as the new head coach. Reynoso, a former player, had been part of the Cruz Azul squad that won their previous league title in the Invierno 1997 tournament. Álvaro Dávila also joined as the club's executive president, with Reynoso as his managerial choice.

The season started poorly for Cruz Azul, with consecutive defeats against Santos Laguna and Puebla, losing both games 1–0. However, the team turned things around in the third matchday, securing a 1–0 away victory against Pachuca. This marked the beginning of an unprecedented 12-match winning streak, tying the Liga MX record set by León in the Clausura 2019. The streak ended with a 1–1 draw against América in Matchday 15.

Despite this, Cruz Azul remained unbeaten for the rest of the regular season, finishing as league leaders with 41 points from 17 matches, an 80% effectiveness rate that also tied León's record from 2019. This dominance set the stage for their playoff campaign.

In the quarterfinals, Cruz Azul faced Toluca. After losing the first leg 2–1 at the Estadio Nemesio Díez, the team rallied with a 3–1 victory in the second leg at the Estadio Azteca, advancing with a 4–3 aggregate. In the semifinals, they encountered Pachuca. After a goalless first leg, a decisive goal by Santiago Giménez in the second leg secured Cruz Azul's place in the final.

The final of the Guardianes 2021 pitted Cruz Azul against Santos Laguna. The first leg, held at the Estadio Corona in Torreón, saw a tightly contested match. Despite Santos Laguna's control over portions of the game, Cruz Azul showcased a solid defensive performance, keeping a clean sheet. Luis Romo's exceptional solo effort resulted in the only goal of the match, giving Cruz Azul a 1–0 lead going into the second leg.

On 30 May 2021, Cruz Azul ended its 23-year Primera División championship drought by beating Santos Laguna 2–1 on aggregate at Estadio Azteca, earning its ninth league title, after having lost seven finals in the last thirteen years.[99][74]

The Martín Anselmi Era (2024)

[edit]On 20 December 2023, Martín Anselmi was appointed as the head coach of Cruz Azul[100] following the departure of former manager Joaquín Moreno, whose disappointing Apertura 2023 campaign saw the club finish in 16th place.[101] Before the start of the Clausura 2024, Anselmi oversaw the signings of key players, including Kevin Mier, Gabriel Fernández, Lorenzo Faravelli and Gonzalo Piovi, raising expectations for the team's performance. Anselmi's first match with the club ended in a 1–0 defeat against Pachuca. Despite this initial setback, he guided the team to a remarkable turnaround, securing a 2nd-place finish in the regular season with 33 points and earning a spot in the Liguilla. During this period, Anselmi posted a video to his personal Instagram that contained Julieta Venegas’s song “Andar Conmigo”, which many supporters viewed as a sign of good luck.[102] In the playoffs, Cruz Azul ended up defeating Pumas UNAM and Monterrey, making it all the way to the Clausura final where they lost to América with a score of 2–1 on aggregate after a controversial penalty was awarded to América after Carlos Rotondi tackled Israel Reyes in the penalty area.[103]

Apertura 2024

[edit]Leading up to the Apertura 2024, Cruz Azul had very high expectations due to them finishing second in the final and table during the previous tournament. Cruz Azul started the season off with a 1–0 win against Mazatlán and maintained an impressive unbeaten streak of six wins and one draw leading up to matchday 8. However, their momentum was halted when they faced Atlético San Luis, suffering a 3–1 defeat that ended their unbeaten streak. Heading into the final matchday of the regular season, Cruz Azul was on the verge of breaking the league record for the most points achieved in a short tournament of 17 matchday games, with 41 points. To set the new record, they simply needed to avoid a loss. On the decisive day, they were facing Tigres UANL, when during the 83rd minute, former Cruz Azul player Uriel Antuna was pulled down in the penalty area by Gonzalo Piovi. The referee awarded a penalty where Nicolás Ibáñez scored putting the game 1–0. During the 98th minute, Cruz Azul captain Ignacio Rivero sent a cross into the penalty area where Ángel Sepúlveda scored from a header, securing Cruz Azul the draw in the dying minutes, and breaking the league record with 42 points.

Crest and colors

[edit]Crests

[edit]-

1927–1964

-

1964–1971

-

1971–1972

-

1972–1973

-

1973–1974

-

1974–1979

-

1979–1980

-

1980–1997

-

1997–2021

-

2021–2022

-

2022–present

Cruz Azul's crest has evolved over the decades, consistently reflecting the club's core identity since its founding in 1927. The blue cross, positioned within a white circle and framed by a red square, has long symbolized the club's heritage and connection to Cooperativa La Cruz Azul, S.C.L., representing the values of unity, resilience, and teamwork. The cross itself is inspired by British influences, as Cruz Azul was originally connected to British culture.[104]

In its early years, the club's emblem was a simple, shield-shaped design centered around the blue cross, a powerful symbol linked to the cooperative roots of the organization. As Cruz Azul grew in prominence, the club refined its emblem in 1964, adopting a rounder design that included the full name, Club Deportivo Cruz Azul. This design marked a shift in the club's identity as it became more established in Mexican football, presenting a more formal, professional image while keeping the cross as its focal point.[105]

The crest underwent another change in the early 1970s following Cruz Azul's first league title. Stars were added above the cross to represent these achievements, and by 1973, the crest displayed three stars, celebrating the team's growing success in the Primera División. This marked the beginning of a tradition where stars were added to commemorate each league title, creating a visual record of Cruz Azul's accomplishments within the emblem. In the years that followed, the club's crest was further refined, with cleaner lines and a modernized look that highlighted the name “Deportivo Cruz Azul” alongside the cross. By 1980, the stars were standardized, and the design streamlined to enhance brand consistency, allowing it to adapt more easily across various media and merchandise. This period solidified the crest's status as one of Mexican football's most recognizable symbols.[106]

As Cruz Azul's prominence grew within Mexican football, the club introduced a significant redesign of its crest in 1997. The emblem was updated to a circular shape, giving it a modern and unified appearance that stood out among traditional club designs. This circular design was complemented by the addition of the word “Mexico” around the outer ring, a declaration of the club's pride in representing the nation at both domestic and international levels. The new shape and wording reinforced Cruz Azul's identity as a symbol of Mexican football, making the crest instantly recognizable and resonant with fans across the country. This design remained largely unchanged for over two decades, becoming a lasting emblem of the club's heritage.[107]

In 2021, Cruz Azul modified its crest to celebrate a significant milestone as the club achieved its ninth Liga MX title, ending a 23-year drought since their previous league title in 1997. This redesign added a ninth star around the emblem, symbolizing the triumph and resilience of the club after years of pursuit. The iconic blue cross remained unchanged at the center, preserving the emblem’s traditional identity while marking this significant moment in Cruz Azul's history.[108] The following year, “Club de Futbol” replaced “Deportivo” around the outer ring, signaling a subtle shift in branding as the club continued to evolve while honoring its heritage. Additionally, the stars encircling the emblem were removed, streamlining the design to focus on the iconic blue cross and the club’s name. This current iteration embodies a forward-looking spirit while remaining grounded in the cooperative principles that have defined Cruz Azul from the beginning.[109]

Colors

[edit]

The colors of Cruz Azul—red, white, and blue—pay homage to the British origins of the company and reflect the club's identity. The blue cross signifies strength and solidarity, while the red and white enhance the visual representation of the club's heritage. This color palette, deeply rooted in the cooperative's history, represents the values of the organization and its commitment to unity within the community. Additionally, the blue, white, and red colors resonate with the symbolism of the Santa Cruz (Holy Cross), further solidifying the connection to the cooperative's mission and identity.[104]

Kit suppliers and shirt sponsors

[edit]| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor (main) | Other sponsors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994–1997 | Azul Sport | Cemento Cruz Azul | None |

| 1997–1998 | Fila | Lada | |

| 1998–2001 | Pepsi and Telmex | ||

| 2002–2004 | Umbro | ||

| 2004–2008 | Coca-Cola and Telcel | ||

| 2008–2009 | Coca-Cola, Telcel and Sony | ||

| 2009–2010 | Powerade, Telcel and Sony | ||

| 2010–2011 | Coca-Cola and Telcel | ||

| 2011–2013 | Coca-Cola, Telcel, Tecate and Volaris | ||

| 2013–2014 | Coca-Cola, Telcel, Tecate and Scotiabank | ||

| 2014–2017 | Under Armour | Boing!, Scotiabank, Telcel and Tecate | |

| 2017–2018 | Scotiabank, Telcel and Tecate | ||

| 2018 | Caliente | ||

| 2019–2023 | Joma | ||

| 2023–2024 | Pirma | ||

| 2024 | Caliente and Cemix | ||

| 2025– | Caliente, Cemix and Bankaool |

Nicknames

[edit]

Cruz Azul has a rich variety of nicknames over its history, listed chronologically:

- Cementeros (cement workers): As a result of affiliation with the Cruz Azul Cement, the first name refers directly to the employees of the company, as the team originally was formed with them. Over the years, the concept is extended not only to those who worked in the cooperative, but the construction workers in general.

- Liebres (hares): When the team was promoted to the Primera División in the mid-1960s, the club played a fast and physical game. These characteristics, coupled with their mostly white uniforms, led fans to compare the players of those years with the hares which abound in the town. The nickname took hold, and an anthropomorphic hare is often used as a mascot and icon to represent the Cruz Azul. While some modern fans believe that the mascot is a rabbit, the club's board has officially declared that it is a hare.

- La Máquina (the machine, the locomotive): This nickname is fed by several sources of inspiration. One is based on a railway that brought the cement from the Cruz Azul plant, in the former village of Jasso (south of Tula de Allende), to Mexico City. After moving to Mexico City, the Cruz Azul was the most dominant club in Mexico during the 1970s, reinforcing the nickname as a comparison to the image of a locomotive sweeping through their opponents. The name may have been borrowed from the similarly nicknamed River Plate club that motored through its opponents in the Argentine Primera División in the 1940s. It has been suggested that reporter Rugama Angel Fernandez was the first to publish an article with the name La Máquina for the Cruz Azul. The nickname has some variations, including The Sky-blue Machine (La Máquina Celeste), The Blue Machine (La Máquina Azul) and The Cement Machine (La Máquina Cementera).

Stadium

[edit]

Cruz Azul originally played at Estadio 10 de Diciembre in Jasso, Hidalgo, from 1964 to 1971. This 17,000-seat stadium saw the club’s first league titles in the 1968–69 and 1970 seasons. Although they left the stadium in 1971, it remained an alternate venue for Copa México, CONCACAF Champions' Cup, and some league matches.[110]

In 1971, Cruz Azul moved to the Estadio Azteca in Mexico City, where they experienced some of their most significant achievements, including five league titles and multiple domestic and international cup victories. They briefly left in 1996 for the Estadio Azul, where they played until 2018. The team returned to the Azteca in 2018, where they won their ninth league title in 2021.[111]

The Estadio Azul, located in Mexico City's Colonia Nápoles, served as Cruz Azul's home from 1996 to 2018. Despite never winning a league title there, it was an iconic venue for the club. After a contract renewal issue, the team returned to the Azteca but announced a temporary return to the Estadio Azul, now known as the Estadio Ciudad de los Deportes, in 2024 due to renovations at the Azteca for the upcoming 2026 FIFA World Cup.[112]

Cruz Azul's second stint at Ciudad de los Deportes lasted one year,[113] as from 2025 the team moved to the Estadio Olímpico Universitario due to logistical issues at the Colonia Nápoles stadium.[114]

The team's training facilities, Instalaciones La Noria, are located in Xochimilco. The team has indicated that it intends to build a new stadium, but solid plans such as location have not materialized.[115]

Support

[edit]

The most recent survey from 2021 placed the club as the 3rd largest fan base in Mexico, behind C.D. Guadalajara and Club América respectively and above UNAM, with 10,9% or 14 million supporters.[116] Historically, since its inception the team was supported mainly by cement workers. After promotion to the Primera División in the 1960s, more people began to follow the team. In the 1970s when the team managed six of their nine titles even more people joined the group of supporters of the team.

The club became infamous in Mexico for not having won a Mexican league title from 1997 to 2021. For an English-speaking audience, the so-called "Cruz Azul curse" is likened to Neverkusen for German team Bayer Leverkusen, the Curse of the Bambino for MLB baseball's Boston Red Sox, or the Curse of the Billy Goat for MLB's Chicago Cubs. The commonality derives from these teams' inability, no matter the quality of the team relative to their opponents in a tournament or a championship match, to win a championship. The "curse" was broken after their winning of the Guardianes 2021 final match versus Santos Laguna, after scoring 2–1 on May 30, 2021. Their title drought also included six losses in finals, among other painful playoff defeats,[117] and spurred the creation of the verb "cruzazulear" which is now used in Mexico to describe choking, or to lose a game when victory was almost assured.[118]

The club had its own official cheerleading club, known as Las Celestes, who were included as part of the institution in 2004. For years, they performed pre-match and during the halftime, becoming a valued tradition of the club and among fans. Cruz Azul was the only Mexican team to officially include cheerleaders as part of its club activities. However, as of today, Las Celestes are no longer active.[119]

Cruz Azul has a passionate fan base, with La Sangre Azul as its only official supporters' group (barra brava in Spanish), recognized by the club. Established in January 2001, it is known for its unwavering support, creating a vibrant atmosphere at both home and away games. Through their chants, banners, and coordinated displays, they play a vital role in uniting fans and enhancing the matchday experience.[120] However, in March 2015, the group lost the support of the club's board due to violent incidents.[121] In recent seasons, though, the relationship with the club's new board has shown signs of improvement, aiming to restore a positive and collaborative connection. La Sangre Azul stands as a key element of Cruz Azul’s fan culture, embodying the loyalty and pride of the club’s supporters.[122]

Rivalries

[edit]Cruz Azul's biggest rival is Club América, with their encounters are famously known as the "Clásico Joven" (lit. 'Young Classic').[123] This rivalry is also deeply rooted in social class distinctions: Club América is often viewed as representing the wealthy and powerful, while Cruz Azul is said to represent the working class,[23] hence fans of Cruz Azul and the team itself being dubiously referred to by the nickname of "Los Albañiles" (lit. 'bricklayers'), a reference to Cruz Azul's eponymous parent company, which is one of Mexico's major companies specializing in concrete and construction.

Personnel

[edit]Management

[edit]| Position | Staff |

|---|---|

| President | |

| Administrative Director | |

| Director of football | |

| Coordinator of football | |

| Director of sports science | |

| Director of academy |

Source: Cruz Azul

Coaching staff

[edit]| Position | Staff |

|---|---|

| Manager | |

| Assistant managers | |

| Goalkeeper coach | |

| Fitness coaches | |

| Physiotherapists | |

| Team doctors | |

Source: Liga MX

Players

[edit]Current squad

[edit]Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

[edit]Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Reserve team's and Academy

[edit]Reserve team that plays in the Liga TDP (Group II), the fourth level of the Mexican football league system.

Defunct teams

[edit]Reserve team that played in the Primera División "A" from 1992 to 2003 and again from 2006 to 2014, and Liga Premier from 2014 to 2021.

Reserve team that played in the Primera División "A" from 2003 to 2006.

- Cruz Azul Jasso

Reserve team that played in the Segunda División from 2006 to 2015.

Reserve team that played in the Segunda División/Liga Premier from 2015 to 2018.

Former players

[edit]Player records

[edit]Tournament top scorers

[edit]- Primera División

| Rank | Name | Season | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1974–75 | 25 | |

| 2 | 1993–94 | 27 | |

| 1994–95 | 35 | ||

| 1995–96 | 26 | ||

| 5 | Verano 2002 | 19 | |

| 6 | Apertura 2009 | 17 | |

| 7 | Guardianes 2020 | 12 | |

| 8 | Clausura 2024 | 8 |

Top goalscorers

[edit]| Rank | Player | Years | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1991–1998 | 198 | |

| 2 | 1971–1982 | 133 | |

| 3 | 1994–2003 | 110 | |

| 4 | 1963–1979 | 92 | |

| 5 | 1971–1977 | 80 | |

| 6 | 2010–2018 | 72 | |

| 7 | 1986–1995 | 71 | |

| 8 | 1977–1986 | 67 | |

| 9 | 2009–2012 | 66 | |

| 10 | 2005–2013 | 63 | |

| 1969–1973 |

Managers

[edit]Managerial history

[edit]| Name | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1961–62 | First coach to manage Cruz Azul in their professional era. | |

| 1962–66 | Promoted the team to the Primera División after winning the Segunda División in the 1963–64 season. | |

| 1966 | ||

| 1966–75 | Won five league titles (1968–69, México 70, 1971–72, 1972–73 and 1973–74), three CONCACAF Champions' Cup titles (1969, 1970 and 1971), one national cup title (1968–69), and two Campeón de Campeones titles (1969 and 1974). | |

| 1975–76 | ||

| 1976 | ||

| 1976 | ||

| 1977–82 | Won two league titles (1978–79 and 1979–80). | |

| 1982 | ||

| 1982–83 | ||

| 1983–86 | ||

| 1986–88 | ||

| 1988 | ||

| 1988–90 | ||

| 1990 | ||

| 1990–92 | ||

| July 1, 1992 – December 31, 1992 | ||

| July 1, 1992 – January 29, 1995 | Second tenure at the club. | |

| 1995–96 | Won the 1996 CONCACAF Champions' Cup. | |

| July 1, 1996 – March 9, 1997 | Won the second national cup title (1996–97 Copa México). | |

| 1997 | ||

| 1997–2000 | Won Cruz Azul's eighth league title (Invierno 1997), against León, and the 1997 CONCACAF Champions' Cup. Lost a league final against Pachuca in 1999. | |

| March 31, 2000 – December 31, 2002 | Led Cruz Azul to the Copa Libertadores final in 2001. | |

| January 1, 2003 – March 7, 2003 | ||

| March 15, 2003 – March 7, 2004 | ||

| March 12, 2004 – October 17, 2004 | ||

| October 19, 2004[128] - December, 2004 | ||

| January, 2005 – December 15, 2005[129] | Kidnapped and held hostage for 65 days during his tenure. | |

| December 15, 2005 – May 20, 2007 | ||

| July 1, 2007 – June 30, 2008 | Led Cruz Azul to a final after nearly 10 years, lost against Santos Laguna. | |

| July 1, 2008 – June 30, 2009 | Lost two finals with Cruz Azul: one against Toluca in the league final, and another against Atlante in the 2009 CONCACAF Champions League final. | |

| July 1, 2009 – June 30, 2012 | Led the team to another league final, but lost against Monterrey, and also reached the 2010 CONCACAF Champions League final, where they were defeated by Pachuca. | |

| July 1, 2012 – December 3, 2013 | Won the third national cup title (Clausura 2013 Copa MX). | |

| December 4, 2013 – May 19, 2015 | Won the 2013–14 CONCACAF Champions League. | |

| June 1, 2015 – September 28, 2015 | ||

| October 2, 2015 – October 22, 2016 | ||

| November 28, 2016 – November 27, 2017 | Led Cruz Azul to first liguilla appearance since Clausura 2014 in the Apertura 2017 season. | |

| December 5, 2017 – September 2, 2019 | Won the fourth national cup title (Apertura 2018 Copa MX), the 2019 Supercopa MX, and led Cruz Azul to the first league final since Clausura 2013. | |

| September 6, 2019 – December 11, 2020 | Won the inaugural edition of the Leagues Cup. | |

| January 7, 2021 – May 19, 2022 | Tied league record for consecutive wins (12). Won the club's ninth league title (Guardianes 2021). | |

| May 30, 2022 – August 20, 2022 | Won the inaugural edition of the Supercopa de la Liga MX. | |

| August 22, 2022 – February 13, 2023 | ||

| February 23, 2023 – August 7, 2023 | ||

| August 8, 2023 – December 19, 2023 | ||

| December 20, 2023 – January 24, 2025 | Broke the record for most league points in a short season (43) |

Honours

[edit]National

[edit]| Type | Competition | Titles | Winning editions | Runners-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primera División/Liga MX | 9 | 1968–69, México 1970, 1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74, 1978–79, 1979–80, Invierno 1997, Guardianes 2021 | 1969–70, 1980–81, 1986–87, 1988–89, 1994–95, Invierno 1999, Clausura 2008, Apertura 2008, Apertura 2009, Clausura 2013, Apertura 2018, Clausura 2024 | |

| Copa México/Copa MX | 4 | 1968–69, 1996–97, Clausura 2013, Apertura 2018 | 1973–74, 1987–88 | |

| Campeón de Campeones | 3 | 1969, 1974, 2021 | 1972 | |

| Supercopa MX | 1s | 2019 | – | |

| Supercopa de la Liga MX | 1s | 2022 | – | |

| Promotion division | Segunda División | 1 | 1963–64 | – |

International

[edit]| Type | Competition | Titles | Winning editions | Runners-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Continental CONCACAF |

CONCACAF Champions Cup/Champions League | 6 | 1969, 1970, 1971, 1996, 1997, 2013–14 | 2008–09, 2009–10 |

| Continental CONMEBOL | CONMEBOL Libertadores | 0 | – | 2001 |

| Intercontinental CONMEBOL CONCACAF |

Copa Interamericana | 0 | – | 1972 |

Regional

[edit]| Type | Competition | Titles | Winning editions | Runners-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Liga MX |

Leagues Cup | 1s | 2019 | – |

| Campeones Cup | 0 | – | 2021 |

- record

- s shared record

Friendly

[edit]- Torneo Almería: 1979[131]

- Torneo Burgos: 1980[132]

- Cuadrangular Azteca: 1981[133]

- Triangular Los Ángeles: 1991

- Cuadrangular Querétaro: 1992[134]

- Torneo Monterrey 400: 1996[135]

- Copa Pachuca: 1997, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2007[136][137]

- Copa 5 de Mayo: 2004

- Copa Panamericana DirecTV: 2007[138]

- Copa Amistad: 2007[139]

- Copa Aztex: 2009[140]

- Copa Socio MX: 2015[141]

- Supercopa Tecate: 2017[142]

- Dynamo Charities Cup: 2017[143]

- Copa GNP por México: 2020[144]

- Copa Sky: 2022[145]

- Copa Fundadores: 2024[146]

Doubles and Trebles

[edit]- Doubles

- League and Copa México (2): 1968–69, 1996–97

- League and CONCACAF Champions' Cup (3): 1968–69, 1970, 1997

- Trebles

- League, Copa México and CONCACAF Champions' Cup (2): 1968–69, 1996–97

Records

[edit]

- Cruz Azul has the distinction of being the only CONCACAF club to win the North American treble twice – winning the Primera División, Copa México, and CONCACAF Champions' Cup in 1969 and 1997.

- Cruz Azul is the Mexican club with the second-most titles at international level, behind only América (six titles in the CONCACAF Champions League, plus a runners-up finish twice in 2009 and 2010, one Leagues Cup title, as well as one runners-up finish in the Copa Libertadores in 2001).

- Cruz Azul is both the Mexican and overall club with the second-most titles in the CONCACAF Champions League, with six (behind only América, with seven).

- Cruz Azul holds the record for most consecutive wins in the history of the Primera División: 12 wins in the Guard1anes 2021.

- Cruz Azul is the Mexican team with the highest number of playoff games played (43), including rounds of reclassification.

- Cruz Azul is the first Mexican team to win a final crown via a "golden goal" (1997).

- Cruz Azul has played (14) and lost (8) the most playoff finals, and has the second-most final wins, with six (tied with Toluca and UNAM).

- Cruz Azul is one of three teams in the history of the Primera División have to win league titles in three consecutive seasons (succeeding in 1971–72, 1972–73 and 1973–74), the other two teams being América, who did so decade later, and Guadalajara.

- Cruz Azul is the fastest team to become champions after being promoted, winning only five years after promotion in the 1968–69 season.

- Cruz Azul became the fastest team to win seven league titles, accomplishing the feat with only fifteen years playing in Mexico's Primera División.

Club statistics and records

[edit]Amateur era (1927–1961)

[edit]During the amateur era, Cruz Azul was composed entirely of employees from the Cruz Azul cement factory, emphasizing the strong bond between the club and its founding organization. The team also frequently achieved high-margin victories over local teams, reflecting their dominance in the league.[147]

- Consecutive titles in the Primera División Amateur del Estado de Hidalgo: 15 titles (from 1935 to 1960), Cruz Azul dominated the amateur league in Hidalgo, winning the title in every season during these years, marking one of the club's most significant achievements.[147]

- First recorded match: Cruz Azul's first match was against Jilotepec, resulting in a 16–0 win.[148]

- Winning streak: Although there is no specific record, Cruz Azul maintained a notable winning streak during its years of dominance in the amateur league.[148]

Professional era (since 1961)

[edit]- Seasons in Primera División: 60, (never relegated since the team's debut in the 1964–65 season)[149][150]

- Seasons in Segunda División: 3[151]

- Playoff (Liguilla) for the title: 60

- Final for the title: 18, (1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74, 1978–79, 1979–80, 1980–81, 1986–87, 1988–89, 1994–95, Invierno 1997, Invierno 1999, Clausura 2008, Apertura 2008, Apertura 2009, Clausura 2013, Apertura 2018, Guardianes 2021, Clausura 2024)

- 1st place: 15

- Relegated to Liga de Expansión MX: 0

- Promotion to the Primera División: 1, (in the 1963–64 season)

- Final position more repeated: 1st, (15 times)

- Best place in Primera División:

- In long tournaments: 1st, (1968–69, México 1970, 1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74, 1978–79, 1995–96)

- In short tournaments: 1st, (Invierno 1998, Invierno 2000, Apertura 2006, Apertura 2010, Clausura 2014, Apertura 2018, Guardianes 2021, Apertura 2024)

- Worst place in Primera División:

- In long tournaments: 18th of 20 teams, (in the 1989–90 season)

- In short tournaments: 18th of 18 teams, (Clausura 2009)

- Highest score achieved:

- The national tournament: 8–2 against Toros Neza (in the 1993–94 season)

- In international tournaments: 12–2 against

Leslie Verdes in 1988 CONCACAF Champions' Cup and 11–0 against

Leslie Verdes in 1988 CONCACAF Champions' Cup and 11–0 against  Seattle Sounders in the 1996 CONCACAF Champions' Cup

Seattle Sounders in the 1996 CONCACAF Champions' Cup

- Highest score against:

- National tournaments: 0–7 against América (Apertura 2022)

- In international tournaments: 1–6 against

Fénix in the 2003 Copa Libertadores

Fénix in the 2003 Copa Libertadores

- Most points in a season:

- In long tournaments: 57, (in the 1978–79 season)

- In short tournaments: 42, (Apertura 2024) (Mexican football record for a 17-game tournament)

- Longest streak of games without losing: 19, (matchday 18 to semifinal second leg in the 1973–74 season)

- Longest undefeated streak at home: 47, (1978–1980) (Mexican football record)

- Most goals scored in a season:

- In long tournaments: 91, (in the 1994–95 season)

- In short tournaments: 41, (Invierno 1998)

- Most wins in a season: 22, (in the 1971–72 season)

- Most draws in a season: 17, (in the 1989–90 season)

- Most defeats in a season: 13, (in the 1982–83 and 1989–90 seasons)

- Consecutive wins in a season: 12, (Guardianes 2021) (Mexican football record)

- More games without conceding: 5, (in the 1975–76 and 1983–84 seasons)

- Most consecutive wins: 12, (Guardianes 2021) (Mexican football record)

- Most consecutive draws: 5, (in the 1973–74 season)

- Most consecutive games without a win: 11, (in the 1965–66 season)

- Fewest wins in a season: 2, (Clausura 2009)

- Fewest draws in a season: 0, (Apertura 2009)

- Fewest defeats in one season: 1, (PRODE 85, Invierno 1998 and Apertura 2024)

- Player with the most goals in a season:

Carlos Hermosillo, 35 (in the 1994–95 season)

Carlos Hermosillo, 35 (in the 1994–95 season) - Most successful manager:

Raúl Cárdenas, won 11 titles with the club:

Raúl Cárdenas, won 11 titles with the club:

- Primera División (1968–69, México 1970, 1971–72, 1972–73 and 1973–74), Copa México (1968–69), Campeón de Campeones (1969 and 1974), CONCACAF Champions' Cup (1969, 1970 and 1971)

- Most successful player:

Fernando Bustos, won 13 titles with the club:

Fernando Bustos, won 13 titles with the club:

- Primera División (1968–69, México 1970, 1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74 and 1978–79), Segunda División (1963–64), Copa México (1968–69), Campeón de Campeones (1969 and 1974), CONCACAF Champions' Cup (1969, 1970 and 1971)

References

[edit]- ^ "Estadio Olímpico Universitario". ligamx.net (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "Mexico City: Cruz Azul to relocate to Azteca – StadiumDB.com". stadiumdb.com. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ "¿Cuáles son los equipos con más finales disputadas de Liga MX y cómo les fue?" (in Spanish). goal.com. 12 December 2021. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "¿Recuerdas la final de Copa Libertadores entre Cruz Azul y Boca Juniors?". TUDN (in Spanish). 12 December 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ "En el futbol mexicano, ¿cuántos equipos han conseguido el triplete?". goal.com (in Spanish). 2020-11-05. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ "What is the treble? Explaining the trophy haul that makes it up as Man City crowned European champions". sportingnews.com. 2023-06-10. Archived from the original on 2024-12-04. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ "World Club Ranking 2014". International Federation of Football History & Statistics. 2015-01-13. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2015-03-25.

- ^ "Esmas.com". Esmas.com. 2008-02-12. Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Olympedia – Carlos Garcés". Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "América Campeón de Liga 1927-28 * Club América - Sitio Oficial". 11 November 2019.

- ^ "El primer campeonato de Liga * Club América - Sitio Oficial". March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-03-16. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "Mexico - International Results Details 1920-1939". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 2022-07-21. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Hace 95 años se estrenó el Tricolor". 9 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b "América y Cruz Azul. Carlos Garcés: Una anécdota compartida". Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "Cruz Azul, el equipo que originalmente era de beisbol y se transformó". 22 May 2020. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "¿Cuál es la fecha correcta de la fundación de Cruz Azul?". 22 May 2019.

- ^ a b "El último testigo de la fundación de Cruz Azul". 4 December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Historia del Cruz Azul". 11 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "PROFMEX-Consorcio Mundial para la Investigación sobre México". Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ a b "Cooperativa La Cruz Azul, S.C.L." Real Estate Market & Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "Cruz Azul y sus 90 años".

- ^ "A Tale of One City: Mexico City". 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b Archibold, Randal C. (25 October 2013). "Mexican Writer Mines the Soccer Field for Metaphors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Cruz Azul, un equipo que nació para brillar". 14 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b Rivas, Shorthand-Edgar. "Cruz Azul y la charla por el título". Shorthand.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cruz Azul". Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "Así nació el Club Deportivo Cruz Azul, "La Maquina Cementera"". 31 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Es la historia de un amor como no hay otra igual: Cruz Azul cumple 94 años de gloria y grandeza". 22 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Guillermo Álvarez Macías - PDF Descargar libre".

- ^ "Cooperativa la Cruz Azul y la Democracia Corinthiana". 22 August 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Recuerdos del ayer". Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "Fallece Luis Velázquez, último testigo del nacimiento profesional de Cruz Azul". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "Fallece Luis Velázquez, último testigo del nacimiento profesional de Cruz Azul". 9 September 2020. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Murió el hombre que cambió la historia: Luis Velázquez 'El Toro', quien llevó a Cruz Azul al profesionalismo". 10 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "La fusión de equipos que originó a Cruz Azul". 28 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "El hombre que no ascendió con Cruz Azul pero siempre estuvo ahí". 19 April 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Cruz Azul: El camino a Segunda División". 17 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Cruz Azul". www.fmf.com.mx.

- ^ a b "Estadio 10 de Diciembre Primer Estadio de Cruz Azul". Archived from the original on 2020-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "CA - Nuestras Raíces - 1953 Reestructuración Socioeconómica". January 30, 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30.

- ^ "Cruz Azul quiere festejar aniversario 94 con el pase a su octava Final". 22 May 2021. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Cruz Azul: Los orígenes". 10 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Álvarez, el apellido que se pinta de azul". Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-09 – via PressReader.

- ^ a b ""Honor y lealtad a nuestra patria, valor y nobleza en el deporte", la frase de Guillermo Álvarez Macías que se convirtió en el lema de Cruz Azul". 23 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Jorge Marik, el técnico húngaro que ascendió a Cruz Azul en el año 1964". 12 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Mexico 1963/64". RSSSF.

- ^ "México - List of Final Tables". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Mexico 1965/66". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 2022-12-06. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Cruz Azul - Plantilla 1965/1966". 30 September 2023. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Azul, Vamos (4 January 2020). "El ex entrenador de la Máquina, Walter Ormeño falleció a los 93 años". Vamos Cruz Azul. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Cruz Azul 1966/1967". Archived from the original on 2021-06-10. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ "¿Quién fue Raúl Cárdenas? El gran entrenador del Cruz Azul". 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Tom Marshall: What now for Copa MX winner Cruz Azul? | Goal.com". www.goal.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ^ "Mexico 1969/70". Archived from the original on 2023-09-23. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Central American Club Competitions 1970". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 2023-02-07. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Cruz Azul fue campeón de la Concacaf en 1970… ¡sin jugar!". 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Recuerdo de Guillermo Álvarez Macías a 42 años de su fallecimiento". 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Guillermo Álvarez Cuevas y su gestión en Cruz Azul". August 2020.

- ^ "Welcome to FIFA.com News - Hermosillo alongside El Tri's best". June 9, 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09.

- ^ "Soccer Star Carlos Hermosillo Joins DEPORTES TELEMUNDO". Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- ^ "Mexico 1994/95". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Central American Club Competitions 1996". RSSSF.

- ^ "View to a Kill". 14 March 2018. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Mexico 1996/97". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 2022-12-09. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Central American Club Competitions 1997". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "¿Por qué pateó Comizzo a Hermosillo y qué fue de él después de eso? | Goal.com". www.goal.com. Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "La verdadera historia: ¿Por qué Brizio no expulsó a Comizzo tras la patada a Hermosillo en la Final del Invierno 97?". 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "¿Cómo fue la final Cruz Azul vs León de 1997? Alineaciones ida y vuelta y marcador global". 30 November 2020. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Mckinley, James C. Jr. (21 July 2005). "Coach Abducted, Adding Focus to Common Mexican Dread". The New York Times.

- ^ Azul, Vamos (7 May 2020). "Rubén Omar Romano revela cómo se rompió su relación con Isaac Mizrahi después de su salida de Cruz Azul". Vamos Cruz Azul.

- ^ a b "Raid ends kidnap for coach". 23 September 2005. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Isaac Mizrahi recuerda cuando asumió la banca de Cruz Azul tras el secuestro de Rubén Omar Romano hace 15 años". 19 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Rubén Omar Romano: El futbol le ha quitado amistades al técnico". www.milenio.com. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b "La "maldición" del equipo de fútbol mexicano Cruz Azul". CNN. 30 May 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Marshall, Tom (29 December 2020). "Think your team is bad? Cruz Azul's name has literally come to define failure, as a verb and in song". ESPN. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Luis E., Morales (28 April 2020). "Cruzazulear, según la Real Academia Española". Te ayudo a comprar. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Cruzazulear". Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ "Santos vs. Cruz Azul - Football Match Summary". ESPN.com. 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Tras dramáticos penales ¡Toluca Campeón del A2008!". Mediotiempo (in Mexican Spanish). 14 December 2008. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Sella Atlante clasificación al Mundial de Clubes, elimina a Cruz Azul". W Radio México (in Mexican Spanish). 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Monterrey conquista tercera corona en México". Reuters (in Spanish). 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Monterrey win Mexican championship". fourfourtwo.com. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Cruz Azul, Campeón de CONCACAF". 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Copa Mundial de Clubes de la FIFA Marruecos 2014 - Cruz Azul-Auckland City FC - Resumen". March 29, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-03-29.

- ^ "Cruz Azul queda fuera de Liguilla por sexto torneo consecutivo". 29 April 2017. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Jémez no renovará para el Clausura 2018" [Jémez will not renew for the Clausura 2018] (in Spanish). 27 November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Paco Jémez deja de ser técnico de Cruz Azul" [Paco Jémez is no longer the coach of Cruz Azul] (in Spanish). 27 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Termina la relación laboral con Eduardo de La Torre" [End of working relationship with Eduardo de La Torre] (in Spanish). 7 May 2018. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Bienvenido Ricardo Peláez Linares" [Welcome Ricardo Peláez Linares] (in Spanish). 7 May 2018. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Peláez llega a Cruz Azul con deseo de ser campeón" [Peláez arrives at Cruz Azul with the hope to become champion]. 9 May 2018. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Los retos de Ricardo Peláez en Cruz Azul" [The challenges for Ricardo Peláez at Cruz Azul] (in Spanish). 8 May 2018. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Arnold, Jon (1 November 2018). "Cruz Azul beats Monterrey to lift Copa MX". Goal. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Cruz Azul owners being investigated for money laundering, links to organized crime". 29 May 2020. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Fiscalía iría por Billy Álvarez y tres directivos más". 30 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Arrest warrant issued for Guillermo Álvarez, president of Cruz Azul". 31 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Billy Álvarez, ex presidente de Cruz Azul, no paga 500 millones de pesos; pisará prisión si es detenido". 11 May 2021. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Interpol is looking for Billy Álvarez in 195 countries". 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Billy Álvarez, ex presidente de Cruz Azul, no paga 500 millones de pesos; pisará prisión si es detenido" (in Spanish). 6 December 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Cruz Azul beats Santos 2-1 on aggregate to end their 24-year championship drought". As. 30 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "¿Quién es Martín Anselmi, el nuevo entrenador de Cruz Azul para el Clausura 2024?". As (in Spanish). 20 December 2023. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Cruz Azul: Joaquín Moreno se DESPLOMA tras FRACASO celeste; "fue muy desgastante"" (in Spanish). 13 November 2023. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Qué relación hay entre Julieta Venegas y el equipo Cruz Azul" (in Spanish). 21 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "Las primeras palabras de Martín Anselmi tras la derrota de Cruz Azul ante América" (in Spanish). 28 May 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ a b "¿Por qué Cruz Azul tiene como símbolo una cruz?". vamoscruzazul.bolavip.com (in Spanish). 22 May 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "¡Qué orgullo! La historia y el origen del escudo de Cruz Azul". vamoscruzazul.bolavip.com (in Spanish). 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "Cruz Azul Logo". 1000logos.net. 3 October 2024.

- ^ "La evolución del escudo de Cruz Azul". goal.com. 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Cruz Azul presume la novena estrella en nuevo jersey para el Apertura 2021". mediotiempo.com (in Spanish). 21 July 2021. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "Cruz Azul presentó oficialmente su nuevo escudo sin estrellas". espn.com.mx (in Spanish). 20 June 2022. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "1953 Reestructuración Socioeconómica" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Cruz Azul termina con su 'maldita' historia y es campeón de México". elfinanciero.com.mx (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "'Estadio Azul' ready to host América and Cruz Azul as Clausura 2024 looms". en.as.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Mexico: Authorities unexpectedly close stadium of three big teams". Stadium DB. 4 November 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "Cruz Azul jugará como local en el Olímpico Universitario". ESPN México (in Spanish). 8 January 2025. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "Mexico City: Cruz Azul still not settled for stadium location". stadiumdb.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "¿Qué equipo de la Liga MX tiene más afición en todo México?". GOAL. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "¡Cómo no te voy a querer! Histórica y épica remontada". TUDN (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Think your team is bad? One club's name has literally come to define failure". ESPN.com. 2020-12-29. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Resultados-futbol.com". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Historia de la barra brava La Sangre Azul y hinchada del club de fútbol Cruz Azul de México". barrabrava.net (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "La Sangre Azul entra por la fuerza a La Noria para hablar con directiva celeste". espn.com.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "La Sangre Azul está de regreso: La nueva administración ya reconoció a la barra de Cruz Azul". vamoscruzazul.bolavip.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ "Encuesta completa sobre el equipo más popular de México". Univision.com. Grupo Reforma. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Primer Equipo Varonil". C.F. Cruz Azul. Archived from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Cruz Azul Plantilla". Liga MX. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Liga MX: ¿Cuántos campeones de goleo ha tenido Cruz Azul en su historia?" (in Spanish). debate. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Los 10 máximos goleadores de Cruz Azul" (in Spanish). Futbol Total. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Saldivar ya entrenó a la Máquina...Fue presentado para lo que resta del torneo". 19 October 2004. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Mizrahi, nuevo DT de Cruz Azul; Romano me dio su apoyo, afirma - La Jornada". www.jornada.com.mx. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ "Palmarés". Club de Futbol Cruz Azul. Archived from the original on 20 September 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Trofeo Ciudad de Almería". reinoazul09. Archived from the original on 19 December 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Trofeo Ciudad del Cid (Burgos-Spain) 1977-1981". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Copa Presidente de Ciudad de México 1981". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 19 December 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.